13-15 September 1999, Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition

Centre

'IP, phone home'

ECMS, (c)-tech, and protecting privacy

against surveillance by digital works

Graham Greenleaf

Professor of Law

University of New South Wales

Australia

http://www2.austlii.edu.au/~graham

g.greenleaf@unsw.edu.au

Abstract

The development of copyright-protective technologies ('(c)-tech') and electronic

copyright management systems ('ECMS'), despite their benefits to rights-hoiders,

pose many dangers to the protection of privacy, which some have said could

mean an end to the privacy of reading. This paper explores these potential

dangers, and possible remedies. How should (c)-tech and ECMS protect privacy

interests? How do existing data protection and privacy laws affect the

operation of (c)-tech and ECMS? Do laws against copyright circumvention

devices and interference with rights management information (RMI) prevent

privacy protection?

Version

This is the first version (26 June 1999) of a work-in-progress, prepared

for the 21st International Conference on Privacy and Personal Data Protection,

Hong Kong 13-15 September 1999. This and subsequent versions may be found

at http://www2.austlii.edu.au/~graham/publications/ip_privacy/

INTRODUCTION - INFORMATION WANTS...

"Information wants to be free"[1]

is one of the 'myths of digital libertarianism'[2]

that formed the ideology of the pre-commercial Internet. Digital libertarians

expected intellectual property law to be one of the first casualties of

cyberspace, because the process of digitisation of works made them infinitely

reproducible at virtually no marginal cost and infinitely distributable

via the Internet. The Internet and property in information were widely

believed to be incompatible, and technology would win against law and set

information free. `Everything [you know] about intellectual property is

wrong' claimed John Perry Barlow[3].

The reverse process is now underway: technical protections of intellectual

property over networks may protect property interests in digital works[4]

more comprehensively than has ever been possible in real space, and destroy

many public interest elements in intellectual property law in the process.

In the worst scenarios, the surveillance mechanisms being developed to

do this may also bring about the end of the anonymity of reading.

As Lessig observes, infinite copies could only be made if "the code

permits such copying", and why shouldn't the code be changed to make such

copying impossible'[5]?

It has only taken a few years for intellectual property to become one of

the most controversial areas where cyberspace architecture is said to be

replacing law as the most effective method of protection, due to the emergence

of copyright-protective technologies (hereinafter '(c)-tech') and electronic

copyright management systems (hereinafter 'ECMS').

This paper explores what protections are found in information privacy

laws against surveillance by digital works, and the extent to which privacy

laws need to be strengthened to help provide a reasonable balance between

privacy and the protection of intellectual property. Some specific questions

are addressed:

-

What are the privacy dangers in (c)-tech and ECMS?

-

How should (c)-tech and ECMS protect privacy interests? Do they?

-

Do laws against copyright circumvention devices and interference with rights

management information (RMI) prevent privacy protection?

-

How do existing data protection and privacy laws affect the operation of

(c)-tech and ECMS?

This paper aks whether we have only received a fragment of Brand's aphorism[6]:

is it really `Information wants to be free ... but it wants to keep you

under surveillance' ?

ANONYMITY AND PRIVACY - TRADITIONAL IP RIGHTS

We should start with a reminder of some of the ways in which intellectual

property laws and enforcement practices have traditionally respected privacy,

so as to appreciate better what changes are inherent in new laws and practices.

Here are some common, though not universal, features:

-

Most sales of artefacts embodying copyright works (books, CDs, videos etc)

were anonymous because they were cash transactions, with payment by identified

means at the option of the purchaser.

-

Users of copyright artefacts did not usually enter into any contractual

relationship with the owner of the copyright, as they dealt only with intermediaries

(booksellers, record stores, libraries etc). This is why copyright was

needed as a property right, since contract was inadequate protection.

-

The artefacts had no inherent surveillance capacities. They would not record

(much less, communicate) who had used them, when or where.

-

Copyright law did not give copyright owners a general right to control

uses of artefacts embodying their works, other than the specified 'infringing

uses' which involved 'copying' and a limited number of forms of communication.

Consequently, who read a book (or watched a film), how often, when

and where was generally none of the author's business.

-

Loans of copyright artefacts to others to use were generally beyond the

control or knowledge of copyright owners. Where intermediaries such as

libraries or video rental stores did keep records of borrowings, these

could result in privacy invasions, but usually not by or for the copyright

owners.

-

Enforcement of copyright - detection of and action against infringing uses

- was therefore not a by-product of routine surveillance of all uses of

copyright works, but usually a matter of selective surveillance and periodic

detection (ex post facto). Enforcement in 'real time' (simultaneous with

attempted infringement) was generally impossible.

-

There were various types of 'fair use' of copyright artefacts (uses which

would normally constitute infringements but under certain conditions did

not) which did not require the user to seek any licence from the copyright

owner or even communicate to the copyright owner that the use was taking

place. 'Fair use' could also be private use.

-

Some types of infringement would only occur where the act concerned was

'in public' (or some similar formulation), effectively creating various

types of 'private spheres' outside the scope of copyright laws[7].

Although these exceptions to copyright for 'private use' are the most obvious

form in which copyright law accommodated privacy, it is a mistake to exaggerate

their importance[8].

In comparison, the default condition of anonymity in the normal use of

copyright artefacts is more important.

The above description was largely true in relation to the 'end users' of

copyright artefacts, consumers, but was less true of various categories

of intermediaries who licensed the uses of copyright works.

THE NETWORKED WORLD OF DIGITAL ARTEFACTS

Kevin Kelly in 'New Rules for the New Economy'[9]

thinks 'the trajectory is clear. We are connecting all to everything.':

As we implant a billion specks of our thought into everything

we make, we are also connecting them up. Stationary objects are wired together.

The nonstationary rest - that is, most manufactured objects - will be linked

by infrared and radio, creating a wireless web vastly larger than the wired

web. It is not necessary that each connected object transmit much data.

A tiny chip plastered inside a water tank on an Australian ranch transmits

only the telegraphic message of whether it is full or not. A chip on the

horn of each steer beams out his pure location, nothing more: "I'm here,

I'm here." The chip in the gate at the end of the road communicates only

when it was last opened: "Tuesday."

Surveillance of what we do via the artefacts that we own or use is a much

broader privacy issue than (c)-tech. Some of the earliest examples have

little to do with intellectual property, but often have to do with protection

of physical property or of other forms of revenue streams. Here are some

examples that are rather more privacy-sensitive than Kelly's, but are not

primarily about protecting intellectual property:

-

Intel planned to put a machine-specific ID in every Pentium III processor

chip, to allow merchants and other "trusted" parties to establish a person's

identity (correlated with their machine ID) over networks, and ostensibly

to prevent stolen PCs from getting on the Internet[10].

From the intended uses, it is fairly clear how broad the 'unintended' ones

could have turned out to be. Intel intended to supply chips with the ID

number feature turned on in default, but with a software patch theoretically

available for those knowledgeable and persistent enough to wish to protect

their privacy - the usual 'opt out' sop. Intel said they would not be keeping

a database matching users to their ID numbers - worthless assurances, as

they could not control manufacturers of PCs with their chips, or large

organisations distributing PCs to users. After a storm of user protest

and threatened legislation, Intel said it would turn off the feature by

default for remaining unsold chips, converting it to 'opt in'.

-

An Australian ISP recently stopped accepting any dial-ins except from lines

that had caller-ID enabled. The ISP claimed it could therefore avoid billing

disputes, but the effect on privacy is to make surveillance of dialing

location a condition of ISP use.

-

Microsoft was forced to change its Windows 98 Registration Wizard after

it was shown to be sending a specific hardware identifier to Microsoft

without user consent[11].

-

The following week, Microsoft's Office 97 was shown to include a secret

unique identifier (derived from the user's network card) in all documents

created with a particular copy. Microsoft claimed that this could not 'reliably'

identify the author of a document[12]

- a rather unconvincing evasion.

There is a trend here: artefacts that report back through digital networks

to some central monitoring point about their location, current state, or

prior usage, often in a way which allows that information to be correlated,

more or less reliably, with the actions of individual people. It is also

a common tactic of the computer industry is to secretly build artefacts

with surveillance capacities enabled in default (at best with some 'opt

out' kludge) and hope they get away with it. Whether this is worse in the

dominant American part of the industry, where developers face relatively

few legislative constraints, deserves to be explored.

If artefacts in general are rushing headlong toward interconnection

through networks, we might expect to see this reflected fairly early in

digitised works. To see that digital artefacts do live in a networked world

is simple enough. Many people now work in offices (or homes) with Internet

connections active whenever they are using their computers. This means

that every program, document or other file on their computer is (in theory)

capable of communicating with anywhere else on the Internet, such as the

computer system of its copyright owner or of an intermediary in an ECMS.

Furthermore, many digital artefacts have their full utility only when we

are online. An obvious example is that word processing documents are now

created routinely with live hypertext links, so that the document is interactive

if opened when the user's PC is online, but not otherwise. The telecommunications

infrastructure for digital artefacts to exercise surveillance is therefore

present, and many of us are increasingly making that infrastructure active

whenever we are at a computer.

Our rights to limit surveillance via artefacts will be one of the key

privacy issues for the start of the next century, and digital works are

likely to be one of the most contentious examples.

TECHNOLOGIES AND SYSTEMS FOR COPYRIGHT PROTECTION

There are a wide variety of particular technologies and products which

can be used to protect digital works (hereinafter '(c)-tech'). We need

to distinguish them from systems of copyright protection which are

built around one or more of these technologies and involve particular sets

of participants (an 'electronic copyright management system' or ECMS).

Copyright-protecting technologies

The variety of (c)-tech[13]

is summarised[14]

below in approximate order of their implications for privacy:

-

Works in a central location, which require a password or some other form

of identification before they can be accessed.

-

Cryptographic `containers' which allow copies of works to be distributed

widely but only used in full once a key has been obtained[15],

or use other metering methods restricting use without further payment ('superdistribution'[16]).

-

Digital watermarks (and other forms of steganography) which embed irremovable

(and sometimes undetectable) information about rights holders and/or licensees

in each copy of the work.

-

Digital works which 'refuse' to allow actions which breach the licence

conditions of that particular copy of the work (Stefik's 'trusted systems').

-

'Trusted printing', where a work will not print (or otherwise copy) unless

payment is first made for the copy, the work is sent to the 'printer' in

encrypted form, and the copies are watermarked in some way. These are part

of 'trusted systems'.

-

Works that cease to be usable after the expiration of a licence or breach

of licence conditions, or until a further licence is obtained.

-

Systems for "detecting, preventing, and counting a wide range of operations,

including open, print, export, copying, modifying, excerpting, and so on"

(part of IFRRO's description of an ideal system).

-

Use of existing internet search engines to search for infringing copies

of works, using normal text searching techniques.

-

Customised web spiders that routinely trawl the web for information identifying

digital works (eg digital watermarks and other identifiers). Such web spiders

are in use[17]

by Broadcast Music Inc (BMI) and by Digimark, a photo watermarking company

acting on behalf of clients such as Playboy.

-

Works that record details of when they are used (including breaches of

licence conditions). IFRRO's ideal system "captur[es] a record of what

the user actually looked at, copied or printed".

-

Works that, whenever they are online, send reports back to a central location

online concerning when are used or copied, including to obtain 'permission'

to do so ("IP phone home"). IFRRO's ideal system sends "this usage record

. . . to the clearinghouse when the user seeks additional access, at the

end of a billing period or whenever the user runs out of credit."

This is an unsystematic and incomplete list of illustrations.

Although there are a bewildering variety of techniques and products

that we could classify as (c)-tech, most seem to combine a few basic elements:

-

Access controls - Controlling access to a work may be as simple

as requiring a password or only accepting http requests that come from

particular sub-domains, or it may require authentication of the enquirer

by a digital signature. Where copies of works are distributed, each copy

may require a separate encryption key to access it (eg 'cryptolopes').

Works may be such that they 'refuse' to allow various forms of use (printing,

'cut and paste', use beyond a certain date etc) unless certain conditions

are met. These are more sophisticated forms of access control.

-

Identification in the work - There are many techniques for embedding

meta-information in the work itself, and many types of information embedded,

from static information identifying the work, its licensee or licence conditions,

to dynamic information that is updated as the work is used.

-

Surveillance - Whatever technologies are used, rights owners (or

intermediaries representing them) often need to some form of active surveillance

of access to and use of the work, either in order to utilise their rights

under copyright law, or for the digital work to execute its own remedies

(eg 'refusing' to operate), or to grant or refuse licences. The information

needed is typically stored in the work itself, but the rights-owner must

access it either through 'pull' methods (eg search engines and web spiders)

or 'push' methods (eg cookies and other means of sending data back to a

central point).

Electronic Copyright Management Systems (ECMS)

Individual (c)-tech are important, but they are not the key element in

the cyberspace architecture that is being developed to protect intellectual

property. What may make architecture replace law as the principal protection

of digital works is a common framework for the trading of intellectual

property rights, both between businesses and to end-users, a set of standards

within which all of the particular (c)-tech can work.

An Electronic Copyright Management Systems (ECMS) may take many forms.

The 'ideal aims' of an ECMS have been described (in a formulation more

sympathetic to consumer and privacy rights than most product descriptions)[18]

as follows:

* provide copyright-protected material to users upon request;

* provide a means for remuneration (or a facility to grant or refuse

a licence) to flow to the owner;

* track usage of material (which documents, how often, used by whom

and so on) without interfering with the privacy of the user;

* prevent unlawful appropriation of the copyright material by people

who are outside the system;

* prevent unlawful use of the copyright material by users who obtain

the material legitimately in the first instance;

* ensure the integrity of the intellectual property;

* allow for a reasonable flow of information between owners to users

(owners are often also users and vice versa) in the public interest (that

is, an ECMS should not unreasonably tie up the community's information

and cultural resources); and

* allow for the effective operation of fair dealing within the ECMS.

The potential for privacy intrusions is apparent from the third, fourth

and fifth aims, even in this 'ideal' description.

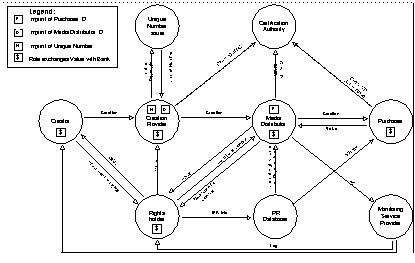

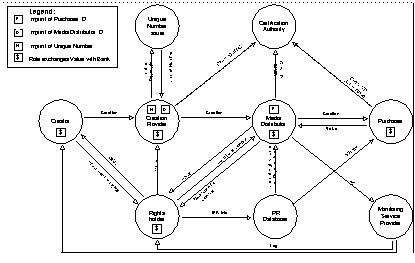

Example of an ECMS model - The Imprimatur Project

In Europe the Imprimatur project[19],

sponsored by the European Commission, developed the Imprimatur Business

Model. Bygrave and Koelman describe the actors and inter-relationships

in the model [20]:

In brief, the role of the creation provider (CP) is analogous

to that of a publisher; ie, he/she/it packages the original work into a

marketable product. The role of the media distributor (MD) is that of a

retailer; ie, he/she/it vends various kinds of rights with respect to usage

of the product. The role of the unique number issuer (UNI) is analogous

to the role of the issuer of ISBN codes; ie, it provides the CP with a

unique number to insert in the product as microcode so that the product

and its rights-holders can be subsequently identified for the purposes

of royalty payments. The role of the IPR database provider is to store

basic data on the legal status of the products marketed by the MD. These

data concern the identity of each product and its current rights-holder.

The main purpose of the database is to provide verification of a product's

legal status to potential purchasers of a right with respect to usage of

the product. As such, the IPR database is somewhat similar in content and

function to a land title register. The role of the monitoring service provider

(MSP) is to monitor, on behalf of creators/copyright-holders, what purchasers

acquire from MDs. Finally, the certification authority (CA) is intended

to assure any party to an ECMS operation of the authenticity of the other

parties whom he/she/it deals. Thus, the CA fulfils the role of trusted

third party (TTP).

Figure - Imprimatur Business Model (Version 2.0)

[21]

From this brief description, some fundamental changes to the way in

which copyright currently operates can be noted:

-

Each digital work is issued with a unique identification number[22],

which is then inserted by the content provided as microcode in the work

to enable it to be tracked in various situations. See below concerning

the range of identification systems emerging.

-

There is an IPR database, `somewhat similar in content and function to

a land title registry', enabling anyone (particularly potential purchasers)

to verify a digital work's ID and legal status.

-

There is a monitoring service provider (MSP) which, on behalf of creators

and rights holders, will (though the summary does not say this) monitor

transactions, uses and breaches (depending on the technology) of rights

in digital artefacts. MSPs will use a variety of mechanisms, including

reporting from Media Distributors, and surveillance of the web through

the use of search engines, customised web spiders, and digital artefacts

that report on their own usage.

-

Certification Authorities (CAs) play a major role, as it assumed that both

parties to transactions, and the authenticity of communications from them

will be routinely identified by digital signatures, and so verification

by CAs is needed.

This blueprint for the architecture in which intellectual property transactions

will operate in cyberspace could hardly be more different than the real

space architecture in which IP operates at present. As regulation, this

code shares few similarities with IP law. This is not necessarily a criticism,

merely an observation of how powerful and different architecture as regulation

will be in intellectual property.

Standards and pervasiveness

The success, importance and danger of ECMS is likely to depend in large

part on the extent to which they achieve interoperability between multiple

publishers (within one ECMS), and ultimately, between different ECMS and

different media types.

One of the key standards is for identification of digital works.

Gervais[23]

describes eleven competing standards, including a variety of media-specific

identifiers, and more general proposals such as the Digital Object Identifier

(DOI) and Persistent Uniform Resource Locators (PURLs). He also describes

five standards for metadata[24]

that (in the absence of one global identification system for digital works

emerging) might provide a basis for interoperability between ECMS based

around different numbering systems. DOI and PURL also have potential for

unifying differing numbering systems without replacing them.

This Babel of IDs for digital works is as yet slowing down the

development of ECMS, and buys a limited amount of time for privacy protection

to be developed.

PRIVACY ISSUES IN (C)-TECH AND ECMS

The amount of online surveillance of users of digital works may become

unacceptable, compared with the ways in which we use intellectual property

in real space.

Bygrave and Koelman, while not opposed to ECMS, stress that the

surveillance dangers are one of the most significant obstacles to their

acceptable operation:

... such systems could facilitate the monitoring of what people

privately read, listen to, or view, in a manner that is both more fine-grained

and automated than previously practised. This surveillance potential may

not only weaken the privacy of information consumers but also function

as a form for thought control, weighing down citizens with "the subtle,

imponderable pressures of the orthodox", and thereby inhibiting the expression

of non-conformist opinions and preferences. In short, an ECMS could function

as a kind of digital Panopticon. The attendant, long-term implications

of this for the vitality of pluralist, democratic society are obvious.

Julie Cohen, speaking mainly of the IFRRO's notion of an ideal ECMS, concludes:

These capabilities, if realized, threaten individual privacy

to an unprecedented degree. Although credit-reporting agencies and credit

card providers capture various facets of one's commercial life, CMS raise

the possibility that someone might capture a fairly complete picture of

one's intellectual life.

Reading, listening, and viewing habits reveal an enormous amount about

individual opinions, beliefs, and tastes, and may also reveal an individual's

association with particular causes and organizations. Equally important,

reading, listening, and viewing contribute to an ongoing process of intellectual

evolution. Individuals do not arrive in the world with their beliefs and

opinions fully-formed; rather, beliefs and opinions are formed and modified

over time, through exposure to information and other external stimuli.

Thus, technologies that monitor reading, listening, and viewing habits

represent a giant leap--whether forward or backward the reader may decide--toward

monitoring human thought. The closest analogue, the library check-out record,

is primitive by comparison. (And library check-out records are subject

to stringent privacy laws in most states. (footnotes omitted)

Gervais, a proponent of ECMS, emphasises the crucial role that ECMS intermediaries

(such as MSPs and CAs in the Imprimatur model) will have in the protection

of privacy:

An electronic copyright-management system does not in and by

itself protect privacy, but it is probably the best tool to do so. If the

rules under which the electronic copyright-management system operates are

correctly designed, the system would return to rights holders aggregated

information on use of his/her works. For example, the system could say

that clearance was granted to use "Scientific Article X" to "11 pharmaceutical

companies in the last month", or that "2,345 users in this part of Chicago"

downloaded a given musical work. The rights holder thus gets market data

without violating anyone's confidentiality or privacy. Even now the Copyright

Clearance Center in the U.S. does not report to rights holders which articles

from medical or scientific journals are used by individual users (e.g.,

pharmaceutical companies). It only tells rights holders how often a work

was used by, say, the pharmaceutical industry as a whole. Most collective

management organizations aggregate information in this way and this is

perhaps a function whose value has thus far been underestimated by users.

Gervais identifies the role of pseudonymity in the proper operation of

ECMS:

A related issue is how to identify individual digital copies

(which presumably have been sold to a specific user), without creating

a risk to privacy or confidentiality. If indeed individual copies are identified,

using a watermark containing a transaction code for instance, a viable

solution could be to number individual copies, without including data identifying

the user who "ordered" the copy in question. Copy numbers could be linked,

in a secure database, to the individual users. Should there be a good reason

to make the link between the copy number and the user -- for instance,

under court order -- that link could be made. The role of trusted third

parties acting as aggregators of usage data might be especially important

to users. An aggregator or collective management organization using an

electronic copyright-management system could thus maintain the confidentiality

of the link (if any) between a given copy delivered on-line and a specific

user. The content owner would receive with the payment for use of his works

a report on the number of uses, possibly with an indication of the type

of users concerned, but no information about individual users. Without

this type of confidentiality guarantee, it may be very difficult for electronic

copyright commerce to prosper. In other words, properly tuned electronic

copyright-management systems that aggregate data so as to protect privacy

and confidentiality are probably essential ingredients of the success of

electronic copyright commerce.

Many other examples may be given of the role that such intermediaries can

play in protecting privacy. Researchers (or lawyers) do not want anyone

to know what digital works they are consulting. An author wanting permission

to include an extract in an anthology or other collection does not want

her publishing plans indirectly disclosed to rival publishers.

Many (c)-tech can be and will be used without any intermediaries between

the end-user of a digital work and the rights-holder. 'Disintermediation'

is still one of the buzzwords of Internet business models. In its positive

incarnations we think of recording artists or authors being able to sell

directly to

their publics. Just as likely, publishing houses of

various sorts (still the rights-holders) will do a far greater percentage

of direct selling to

the public without the use of intermediaries

such as booksellers (Amazon excepted!). The result is likely to be a mixture

of delivery models, but the point is that a lot of (c)-tech and ECMS will

be run directly by publishing houses with lots of different products to

shift and a strong interest in secondary use of identified consumption

data. We will not always be 'lucky' enough either to have some central

industry-based monitoring body standing between consumers and publishers,

or to be dealing direct with the artist.

Without attempting to catalogue the issues at this point, it seems

that privacy protection in relation to (c)-tech and ECMS must have multiple

aims. First, there is a need to maximise the use of (c)-tech which allows

fully anonymous transactions involving digital works, provided that in

doing so we don't create worse problems of unfair contract enforcement

(see below). Second, where it is necessary for transactions to be identifiable,

pseudonymity should be used wherever possible to prevent the misuse of

personal information for secondary purposes, and also to prevent a 'chilling

effect' on freedom to read, think and speak.

Other issues in ECMS - 'fair use' and fair enforcement

Privacy is not the only issue raised by ECMS, nor perhaps even the most

important one. The architecture of ECMS need not observe any of the public

interest limitations built in to copyright law. These include the right

to lend a work for use by others (the basis of libraries - the `first sale

doctrine'), and the various `fair dealing' rights to copy works or parts

thereof for purposes such as `criticism and review' or `private study and

research'. As Lessig puts it "what the law reserves as an limitation on

the property holder's rights the code could ignore"[25].

If dealings in relation to digital works become direct transactions where

it is practical for the rights-owner to enter into a contract with the

user (unlike the purchase of a book in a store), then such contracts are

likely to routinely exclude such public interest exceptions.

The enforcement of such contracts is also unlike real space contracts,

Lessig points out[26],

because whereas the law always takes into account various public and private

interests in determining the extent and means by which contracts will be

enforced, when contracts are self-enforced by code (for example, by the

work suddenly becoming unusable) these public values are not likely to

be taken into account. We might add that when the law enforces a contract

there is an independent assessment of whether there has been a breach of

the contract, whereas here the enforcement is automated and unilateral,

built into the architecture. If `code contracts' replace law, these are

not necessarily the same as `law contracts', and may not be in the public

interest.

Are ECMS addressing privacy issues?

It is difficult to the sure to what extent those who are developing ECMS

are taking privacy issues seriously. A list of over 30 ECMS projects[27]

does not contain any with privacy policies explicitly listed on their web

sites, though this may sometimes be because their proposed operations are

not privacy-sensitive. However, it is surprising not to find easily accessible

privacy policies on such major sites as Open Market's SecurePublish[28]

(a Folio product) or Copyright Clearance Center[29].

It would be helpful (and probably reassuring) if major players in (c)-tech

and ECMS had easily accessible privacy policies concerning the use of their

products and services. Imprimatur commissioned the valuable Report by Bygrave

and Koelman, but research on privacy implications by other promoters is

hard to find.

The Propagate project[30],

Australia's equivalent to Imprimatur, held its first Consensus Forum (August

1998) with the aim of developing 'consensus' within the Australian `rights

community' on development of ECMS standards for all media types in Australia.

Most collecting societies and other rights-holder organisations attended,

but there was little representation of the users of copyright works, or

of the broader public interests that copyright serves. As Lessig puts it

`once it is plain that code can replace law, the pedigree of the codewriters

becomes central'. This 'consensus' approach, though valuable, is not genuinely

representative of the interests affected. The discussions at the Forum

showed a lively sensitivity to privacy considerations, and recognition

of the value of anonymous and pseudonymous transactions, but there fewer

ideas on how to accommodate the `fair dealing' issues mentioned above.

LAWS AGAINST CIRCUMVENTION OF COPYRIGHT PROTECTION

The WIPO Copyright Treaty 1996 (WCT) requires contracting parties

to provide legislative prohibitions against copyright circumvention devices

and against the removal of 'rights management information' (RMI). These

are the first legislative protections given to (c)-tech and ECMS, by the

negative device of preventing their circumvention. Although phrased in

terms of protecting an author's statutory rights, they may turn out to

be of broader significance as one of means by which authors can protect

an expanded set of rights through a combination of contracts and surveillance.

This is law facilitating surveillance: 'data surveillance law'.

Article 11 provides, in relation to copyright circumvention devices:

`Contracting Parties shall provide adequate legal protection

and effective legal remedies against the circumvention of effective technological

measures that are used by authors in connection with the exercise of their

rights under this Treaty or the Berne Convention and that restricts acts,

in respect of their works, which are not authorised by the authors concerned

or permitted by law.'

Article 12 of the WCT provides, in relation to 'rights management information':

(1) Contracting Parties shall provide adequate and effective

legal remedies against any person knowingly performing any of the following

acts knowing, or with respect to civil remedies having reasonable grounds

to know, that it will induce, enable, facilitate or conceal an infringement

of any right covered by this Treaty or the Berne Convention: (i) to remove

or alter any electronic rights management information without authority;

(ii) to distribute, import for distribution, broadcast or communicate to

the public, without authority, works or copies of works knowing that electronic

rights management information has been removed or altered without authority.

(2) As used in this Article, `rights management information' means information

which identifies the work, the author of the work, the owner of any right

in the work, or information about the terms and conditions of use of the

work, and any numbers or codes that represent such information, when any

of these items of information is attached to a copy of a work or appears

in connection with the communication of a work to the public.

From the perspective of privacy protection, some of the questions we need

to ask about these provisions and their national legislative implementations

are:

-

Can you delete from digital works personal information that facilitates

surveillance?

-

Can you prevent a web robot from looking for infringing artefacts?

-

Can you prevent a digital work from communicating information over the

Internet?

National implementations of the WCT are what is crucial, and they may go

beyond what it requires. In the following sections, we will take Australia

as an example of implementation. The United States Digital Millenium

Copyright Act of 1998 has amended Title 17 of the US Code (dealing

with copyright) to implement the WCT. Where the US has taken a different

approach to protection of privacy, this is noted but not analysed in detail.

Example - Australia's 'Digital Agenda' Bill

The Australian Government intends to ban commercial dealings in circumvention

devices and to ban removal of copyright information (`rights management

information') electronically attached to copyright material' [31]

. A draft Copyright Amendment (Digital Agenda) Bill 1999 has been

given a first reading in Parliament.

Circumvention devices

The Bill draws heavily on the proposed EC Directive[32],

and so is of interest as a comparative implementation of the Directive

as well as of the WCT. It is a breach of copyright where a person makes,

sells, imports or otherwise deals with[33]

'a circumvention device[34]

capable of circumventing, or facilitating the circumvention' of 'effective

technological protection measures', if they knew or were reckless as to

whether it would be used for this purpose and for the purpose of infringing

copyright (s116A). The onus of proof rests on the defendant. Where s116A

applies, the copyright owner has the same remedies against the person responsible

for the circumvention device as in relation to any infringements of copyright

as take place.

There will also be a criminal offence where the same conditions

as in s116A are satisfied, but with a higher burden of proof and the onus

of proof on the Crown (added to s132). A similar offence is created in

relation to the operation of a 'circumvention service'[35].

The Australian legislation is principally interesting from a privacy

perspective because of its limited scope:

-

Actual use of a circumvention device is not proscribed, only making

and dealing in such devices. Nevertheless, a question remains as to whether

a person who writes his or her own small piece of software in order to

prevent some surveillance device operating as it is intended might be regarded

as 'making' a device.

Provision of a 'circumvention service' is a criminal offence, but

it is not an offence (or an infringement) simply to use such a service.

An ISP would have to consider whether it was providing 'circumvention services'

to those whose content it hosts or to whom it provides access.

-

While the definition of 'technological protection measure'[36]

is broad, only 'effective technological protection measures'[37]

are protected, and these are limited to measures where 'access to the work

or other subject-matter ... is available solely by use of an access code

or process (including decryption, de-scrambling or other transformation

of the work or subject-matter) with the authority of the owner of the copyright

in the work or subject-matter. The Bill will protect the use of (c)-tech

aimed at access limitation such as 'crypto-bottling' of works (where access

depends on use of a particular decryption key) or the simple device of

providing on-line (or CD-ROM) access only by password. Technologies to

make digital artefacts expire after use or after a period could also be

protected here.

It is a possible that a digital artefact resident on a user's PC

which could not be accessed unless there was first an online check back

to the copyright owner's database that the licence was still valid ('IP,

phone home') could be regarded as an 'access ... process' protected by

this provision. If so, one of the most far-reaching forms of surveillance

by and of digital works will be protected. The important thing to note

is that circumvention will be illegal irrespective of whether the personal

information which is collected is used for secondary purposes (eg marketing)

which have nothing to do with copyright protection, and whether or not

normal privacy protections in the collection of personal information have

been observed (see the next section). In short, anti-circumvention provisions

are applicable irrespective of privacy breaches, and they should not be.

The US

Digital Millenium Copyright Act provides an explicit defence

agains its anti-circumvention provisions where circumvention is only for

the purpose of protection of personally identifying information[38].

-

A piece of (c)-tech could not 'know' that the purpose for which a user

wished to use a work was a 'fair use' and therefore there was no need to

check whether access was licensed (because no licence is needed). If a

user made a circumvention device for this purpose this would not be illegal,

because it is not for the purpose of breaching copyright[39].

This is good, but if someone makes and distributes a device to assist others

to preserve the privacy of fair use, will they still be 'reckless' as to

its possible use to conceal infringements? Or will they be able to argue

that their device has more than 'only a limited commercially significant

purpose' for non-infringing use? Protecting the privacy of fair use remains

perilous under these proposals[40].

-

However, other privacy-sensitive (c)-tech will not infringe copyright.

A web spider checking for copyright items is not a limitation on access

to those items. A digital watermark or similar device, even if it does

include details of the identity of the licensee, does not prevent access.

Devices or services that circumvent such protections are therefore not

a breach of this prohibition.

-

Circumvention devices and services are restricted to those that have 'only

a limited commercially significant purpose or use other than the circumvention'.

So, for example, if an ISP excluded all web robots from its site[41]

(which may host many other content sites) then this would not be a breach

(even if - as is unlikely - such a robot was an 'effective technological

protection measure') because such a service or exclusion has many other

commercially significant purposes and uses, such as reducing system load.

In summary, the Australian legislation is limited in its effect on privacy,

but may still make it illegal for people to provide protection against

invasions of the privacy of 'fair use', and to protect against the secondary

misuse of personal information collected via (c)-tech.

Rights management information

In relation to rights management information (RMI), s132(5D) of the Bill

makes it a criminal offence to 'remove or alter any electronic rights management

information attached to a copy of a work', provided there is the required

intent[42].

There are related offences concerning distributing, importing and communicating

artefacts where such information has been removed or altered (s132(5E)).

'Electronic rights management information' is defined in terms

very similar[43]

to those in the WCT Article 12(2) and the WPPT Article 19[44].

Some of the implications of the provisions for privacy-sensitive uses

are:

-

The definition of RMI does not explicitly refer to information identifying

the licensee / owner of the work, and Bygrave and Koelman have interpreted

the WTC definition as not including information identifying users such

as the Purchaser ID (in the Imprimatur model)[45].

However, this interpretation is questionable, as both the WCT and Australian

definitions of RMI include 'conditions' on which a work may be used. If

a work has been licensed on the basis of a 'single user' licence to a specified

individual, it is hard to see why the identify of that individual is not

part of the conditions of use. In comparison, the US Digital Millenium

Copyright Act provisons defining 'copyright management information'

imply that any information concerning users is not included[46].

However, any information about users is not a necessary part of

a condition of use is not RMI and can be removed.

-

The definition of RMI only protects information which (in the Australian

version) is 'attached' to the work. The protection of RMI would therefore

not extend to the prevention of blocking the online transmission of RMI

back to some central collection point ('IT, phone home') each time the

work is used. This interpretation is also supported by the use of 'remove'.

We can therefore see the RMI provisions as protecting the passive storage

of RMI, but not its active dissemination.

-

The definition of RMI does not refer to information about actual usage

of a work, but only to its 'conditions' of use. Ongoing collection of actual

usage information by a digital work is therefore not protected.

-

The Australian provision does not allow removal of RMI 'except with the

permission of the owner of the copyright' whereas Article 12 of the WCT

only requires prevention of removal 'without authority'. Bygrave and Koelman[47]

argue that in the EU context such authority could come from what is permitted

or required by law (such as laws implementing the EU privacy Directive).

The RMI provisions therefore seem to avoid the worst threat to privacy,

in that they do not make it compulsory for users to accept active surveillance

and reporting by digital artefacts that reside on their computers.

Conclusions

We can summarise the above discussion with some tentative answers to the

questions with which we started:

-

Can you delete from digital works personal information that facilitates

surveillance? If the information is necessary as part of the terms

of a user licence, you probably can not because it is protected RMI. Other

personal information can be removed.

-

Can you prevent a web robot from looking for infringing artefacts?

Under Australian law this will not constitute a circumvention device or

service (even if only 'IP bots' are excluded), and in any event general

methods of excluding robots are exempted as they have other significant

commercial uses.

-

Can you prevent a digital works from communicating information over

the Internet? Under Australian law it is possible that some forms of

such communication will be an 'access ...process' protected against circumvention

devices and processes. Whether protecting the privacy of 'fair use' is

exempted is hard to judge. Protecting against the secondary misuse of personal

data collected via (c)-tech is not an exception. Other communications by

digital works that merely report on usage but do not control access may

not be so protected. The communication of such information does not constitute

RMI.

If the Australian example is indicative, laws facilitating technological

protections of copyright will have a very complex relationship with privacy

interests. The WCT Articles 11 and 12, and their Australian implementation,

do not go so far as to constitute an unrestricted 'licence for surveillance'

of our hard disks and usage habits. But it seems that the essential surveillance

task, online checking of entitlement to use digital artefacts, is protected.

IP can phone home to check that she should still be at your place, and

it would be criminal to try to stop her.

THE EFFECTS OF PRIVACY LAWS

Having considered the extent to which copyright laws are facilitating surveillance,

we now need to complete the picture by asking to what extent do existing

data protection and privacy laws impose limits on the operation of (c)-tech

and ECMS in order to protect privacy?

The United States is a special case (as yet). TheDigital Millenium

Copyright Act contains explicit provisions limiting the operation of

the anti-circumvention and RMI-protection provisions where they would infringe

privacy, as mentioned above. Julie Cohen's arguments[48],

prior to the enactment of that law, that laws prohibiting copyright circumvention

devices diminish 'the right to read anonymously' and may breach the guarantees

of freedom of speech and privacy in the US Constitution are of limited

relevance as legal arguments to countries which do not have such constitutional

guarantees, though they are valuable as arguments concerning desirable

policy. Most European and some other countries are more willing than the

USA to protect privacy by general information privacy legislation. In many

other countries, there is likely to be less reluctance to interfere in

'private orderings' of transactional relationships concerning intellectual

property by legislation, for example by compulsory licensing schemes. Even

in the USA, compulsory terms in such contractual relationships are not

so unusual[49].

Because of these US complexities, we focus here on the sets of information

privacy principles found in European and other laws as a potential source.

There is a detailed discussion in Chapter 2 of Bygrave and Koelman's study,

concentrating on EU laws and the EU privacy Directive, and the particular

example of the Imprimatur model.

Is ECMS data 'personal information'?

Most data protection laws only protect 'personal data' or 'personal information',

requiring that the information be capable of being linked to an identifiable

individual. However, legislation usually allows the data in question to

be combined with other data to produce this identification, but expresses

how this combination may be achieved in different ways. For example, in

Australia's Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) 'personal information' means

any information 'about an individual whose identity is apparent, or can

reasonably be ascertained, from the information or opinion' in question

(s 6).

In many cyberspace transactions, what will constitute 'personal information'

is uncertain, and this may have a severe effect on the applicability of

data protection laws to those transactions. In an analysis of the Australian

law [50],

I concluded that whether machine addresses and email addresses would constitute

personal information would usually be a question of fact in a particular

case. Bygrave and Koelman also though this was uncertain[51].

In the ECMS context, there may be many doubtful situations. For example,

if a web spider merely collects the ID number of a licensed digital work,

but it is possible for that ID number to be subsequently correlated (perhaps

via a number of steps) with the identity of the individual who holds the

licence, has the web spider been involved in the collection of personal

information? It will also be doubtful whether, if information is accessible

on a web page, it can be 'personal information' at all (because it is potentially

available to the public), but this will depend on the wording of particular

legislative provisions[52].

However, these types of definitions may miss the real point of

many cyberspace interactions. If an ECMS can determine that a copy of a

digital work it has located on the net is an infringing copy, or is being

used in breach of its licence, and it can initiate enforcement action without

knowing the identity of the person who is responsible, it has acted against

an individual and with serious consequences. For example, if a digital

work merely sends 'back to base' information about the PC on which it is

located, or the internet sub-domain on which it resides, but there is no

record in the rights-owner's database of a licence in relation to those

locations, so that the work automatically ceases to be usable, where is

the collection or use of personal information? Similarly, if information

about the reading habits of a pseudonymous licensee can be aggregated so

that it is commercially valuable to market other digital works to that

individual, and there is access to an email address which makes this possible,

the publisher has no need to know the identity of the individual marketed

to.

Limits on collection

Many aspects of data collection by ECMS will be with the consent of the

data subject, or pursuant to a contract with the data subject. They will

therefore have to comply with the normal requirements of disclosure of

purpose, and limitations on excessive collection (which could be significant

for ECMS)[53].

More contentious forms of collection of personal information are

likely to arise because of the surveillance aspects of ECMS. If a monitoring

service provider (MSP) uses a web spider solely for the purpose of collecting

rights management information (RMI), or if the digital work sends reports

back to the MSP, it may be collecting 'personal information' (see discussion

above). The MSP may be in a contractual relationship with the person concerned

(a licensee), but questions may arise as to whether the collection is with

consent, or (in EU Directive terms) the collection is necessary for the

performance of the contract or for the purpose of the legitimate interests

of the MSP or its client. Disclosure of surveillance practices at the time

of contract may be necessary, as it may be impossible at the time of collection

(for example, collection by web spiders).

If the person whose personal information is collected has no relevant

contractual relationships (for example, a person whose machine address

is disclosed as the location of a digital work) then there will be no consent

to collection and no contract, so justification for collection may be more

difficult to provide.

The Working Party On The Protection Of Individuals With Regard

To The Processing Of Personal Data set up under the EU privacy Directive

(hereinafter 'the Article 29 Committee') made recommendations in February

1999 concerning automated processing which is unknown to the user[54]

which are relevant to the collection of data by ECMS and (c)-tech. The

recommendations are expressed as applying to 'internet hardware and software

products'. It would be better if they also applied expressly to digital

works, as the issues are the same, but it is straining language to call

a digital artwork 'software'. All five recommendations are relevant (I

have substituted 'digital works' for 'software' in discussing them):

-

Processing of personal data by digital works which occurs without the knowledge

of the data subject is not legitimate processing (Recommendation 1). Examples

of where this may occur are given above.

-

Digital works should provide Internet users with information about 'the

data that they intend to collect, store or transmit and the purpose for

which they are necessary' (Recommendation 2). Where cookies are used, they

say, users should be informed whenever a cookie is to be received, stored

or sent, and in generally understandable language. Germany's Teleservices

Data Protection Act already provides such a requirement of notification

before processing commences (s3(5)).

-

Default configurations should not 'allow for collecting, storing or sending

of client persistent information'. This means that, in default, browsers

should only send the minimum information needed for communication, and

should in default refuse to receive cookies (Recommendation 3). Who controls

the default settings of cyberspace architecture is one of the key regulatory

issues in cyberspace[55].

-

Users should be able to 'freely decide' about the processing of their personal

data, and modify what items are processed (Recommendation 4).

-

Users should be able 'to remove client persistent information in a simple

way' (Recommendation 5). One problem with applying this to digital works

is that it could result in a breach of copyright laws protecting RMI (see

discussion above).

Recommendations 3-5 seem inconsistent with many possible implementations

of technological protection of digital works, where it is an essential

part of the protection of the work that the user does not have a choice

but to submit to surveillance as a condition of licensing the work. Will

rights-owners be allowed to require such conditions?

Limits on use and disclosure

The finality principle has significant implications for the operation of

ECMS. Secondary uses, particularly marketing uses, are analysed by Bygrave

and Koelman[56],

who note a number of provisions which could have a significant effect on

ECMS operations:

-

Article 15(1) of the EU privacy Directive gives persons the right not to

be subject to decisions based on automated processing which evaluates personal

information. If a (c)-tech terminated the usability of a digital work because

of automated processing of information about breaches or expiry of a licence,

it could be caught if the information processed included personal information.

The processing would have to be shown to be done pursuant to a contract,

and even then would have to be within the data subject's reasonable expectations.

-

Germany's Teleservices Data Protection Act prevents the aggregation

in an identifiable form of personal information relating to the use of

several teleservices by one user (s4). Such a restriction would significantly

limit the secondary uses of ECMS information.

Anonymity and pseudonymity as privacy rights

A key privacy issue is whether ECMS are designed so as to maximise the

availability of anonymous or pseudonymous transactions. Germany's

Teleservices

Data Protection Act[57]

is an early legislative example of `systemic data protection' (`Systemdatenschutz').

We can also call `legislating cyberspace architecture'. It requires the

objective of minimising or eliminating the collection and use of personal

information to be built into the `design and selection of technical devices'

(hardware and software):

-

The design and selection of technical devices to be used for teleservices

shall be oriented to the goal of collecting, processing and using either

no personal data at all or as few data as possible.'

It is this design requirement that makes the specific requirement on service

providers to provide anonymous and pseudonymous uses of teleservices 'to

the extent technically feasible and reasonable'[58]

a meaningful requirement, because it removes the excuse that systems have

not been designed to allow for anonymous or pseudonymous transactions.

Here, the control of architecture by law is both a serious, though general,

limitation on the types of Internet systems that may be built, and a necessary

precondition for legal sanctions aimed directly at the behaviour of service

providers.

In Australia the `anonymity principle' has been making progress

toward becoming a legal requirement of cyberspace architecture. Its local

origins lie in Principle 10 of the Australian Privacy Charter (1994):

`People should have the option of not identifying themselves when entering

transactions'[59].

In 1998 the Australian Privacy Commissioner's National Principles for

the Fair Handling of Personal Information[60]

included Principle 8 'Wherever it is lawful and practicable, individuals

should have the option of not identifying themselves when entering transactions'.

The Victorian State Government has included this Principle in its Data

Protection Bill 199961(with 'should' changed to 'must'),

and these Principles are now being included in national legislation being

drawn up for the whole private sector. One of the main differences between

this Australian formulation and that in the German law is that it does

not have the explicit legislative requirement for systems to be designed

to allow anonymity and pseudonymity. The Victorian provision might therefore

be interpreted to allow the excuse that it is not `practicable' because

the system design makes it technically impossible. However, the strong

wording of 'must have the option' may be interpreted to at least require

any systems designed after the legislation commences to provide anonymity

and pseudonymity options wherever 'practicable'.

It is possible for many aspects of ECMS and (c)-tech to be designed

so that pseudonymity (and in some cases anonymity) of licensees can be

preserved, while still protecting the core economic interests of rights-holders.

However, the secondary economic interests of rights-holders (or intermediaries)

in being able to exploit the personal information that they obtain from

ECMS are in direct conflict with rights of anonymity and pseudonymity.

Issues of purpose specification will be crucial.

The Article 29 Working Party has made recommendations concerning

anonymity on the Internet[62].

The following main conclusions are relevant here:

* The ability to choose to remain anonymous is essential if individuals

are to preserve the same protection for their privacy on-line as they currently

enjoy off-line.

* Anonymity is not appropriate in all circumstances. Determining the

circumstances in which the 'anonymity option' is appropriate and those

in which it is not requires the careful balancing of fundamental rights,

not only to privacy but also to freedom of expression, with other important

public policy objectives such as the prevention of crime. ...

* Wherever possible the balance that has been struck in relation to

earlier technologies should be preserved with regard to services provided

over the Internet.

* The ... purchase of most goods and services over the Internet should

all be possible anonymously. ...

* Anonymous means to access the Internet (e.g. public Internet kiosks,

pre-paid access cards) and anonymous means of payment are two essential

elements for true on-line anonymity.

The Working Party's conclusions show a clear preference for maximising

anonymity in Internet transactions, subject to balancing this with other

rights. They recommend that where appropriate the 'minimum necessary collection'

principle 'should specify that individual users be given the right of anonymity'.

A surprising limitation of the Working Party's approach is that it does

not adequately distinguish anonymity and pseudonymity, nor pursue the extent

to which pseudonymity should be offered where anonymity is not practicable[63].

ECMS intermediaries can use pseudonymity in order to maintaining their

ability to identify copyright infringements of digital artefacts, while

preventing secondary use of the identifiable information by rights owners.

Data export prohibitions

ECMS are likely to involve large-scale flows of personal information between

jurisdictions, as many will operate on an international scale. Where the

end-users are located in Europe (and some other jurisdictions) data export

prohibitions may apply where personal data is collected by ECMS surveillance

facilities. In many instances the exceptions in Article 26 of the EU privacy

Directive will apply[64],

but there are likely exceptions such as collection by web spiders and other

situations where (c)-tech may operate outside contractual relationships.

CONCLUSIONS - DO WE NEED PROTECTION FROM COPYRIGHT?

What privacy protections are needed? - a beta list

Large-scale implementations of (c)-tech and ECMS are still in a sufficiently

early stage that it is premature to offer more than a speculative list

of what protections may be needed as the technologies and business models

mature. Here is such a beta list, offered to provoke discussion:

-

'Anti-circumvention' copyright protections require defences or exceptions

to allow the use of devices to protect privacy against secondary misuses

of personal information and to allow 'fair use' to remain private use.

-

Protections of rights management information (RMI) should not require individuals

to submit to active active online surveillance and reporting by digital

works on their computers.

-

Defences for removal of RMI should include various forms of legal justification,

not only the consent of the rights-owner.

-

System designers should be required to maximise the use of (c)-tech which

allows fully anonymous transactions (balanced against problems of unfair

contract enforcement).

-

Where it is necessary for transactions to be identifiable, pseudonymity

should be allowed wherever possible.

-

Definitions of 'personal information' and the like may need strengthening

to apply to more cyberspace transactions affecting indviduals.

-

Restrictions on collection of personal information may need strengthening,

to ensure that notification rights are effective.

-

Default configurations of digital works should not enable surveillance

capacities.

-

Restrictions on the misuse of personal information for secondary purposes

need checking to ensure that apply in this context.

What can privacy officials do?

National data protection and privacy Commissioners need to take steps in

their own jurisdictions, if they have not already done so, including:

-

Encouraging developers and vendors of (c)-tech and ECMS in their own jurisdiction

to develop and publish privacy policies.

-

Enforcing, where appropriate, data protection laws against the local implementations

of (c)-tech and ECMS, particularly in relation to the provision of anonymity

/ pseudonymity options.

-

Taking an active role in local debates on legislation concerning circumvention

devices and RMI, to ensure that consumers (and creators) are not made subject

to compulsory surveillance by digital works.

-

Engaging in dialogue and education of the local IP community to ensure

that authors, publishers and the public are sensitive to the privacy issues

involved in (c)-tech and ECMS. Consumer organisations are starting to express

concern[65]

and should be included in any dialogues.

A task for the Article 29 Committee?

The Article 29 Committee has taken a leading role as a multi-national policy-making

body of data protection and privacy Commissioners, and has already published

conclusions and recommendations that are very relevant to this area. It

seems an appropriate forum for the development of international standards

for the protection of privacy in the use of (c)-tech and ECMS, particularly

in relation to their compliance with the Directive. The recently-established

multi-disciplinary Internet Task Force of the Committee should have as

one of its priority tasks the development of recommendations concerning

privacy protection in ECMS and (c)-tech, and how they are to be reconciled

with the anti-circumvention provisions in international copyright agreements.

REFERENCES

-

Article 29 Commmittee (1999a) The Working Party On The Protection Of Individuals

With Regard To The Processing Of Personal Data Recommendation 1/99 on

Invisible and Automatic Processing of Personal Data on the Internet Performed

by Software and Hardware (23 February 1999) - <http://europa.eu.int/comm/dg15/en/media/dataprot/wpdocs/wp17en.htm>

-

Article 29 Committee (1997a) The Working Party On The Protection Of Individuals

With Regard To The Processing Of Personal Data Recommendation 3/97 Anonymity

on the Internet (3 December 1997) - at <http://europa.eu.int/comm/dg15/en/media/dataprot/wpdocs/wp6en.htm>

-

John Perry Barlow (1993) `Selling Wine Without Bottles: The Economy of

Mind on the Global Net' Wired 2.03 (1993) at 86 - at <http://www.eff.org/pub/Publications/John_Perry_Barlow/HTML/idea_economy_article.html>

(visited 19/10/98).

-

Lee Bygrave and Kamiel Koelman (1998) Privacy, Data Protection and Copyright:

Their Interaction in the Context of Electronic Copyright Management Systems

Institute for Information Law, Amsterdam, June 1998 at p5 (Report commissioned

for the Imprimatur project) - <http://www.imprimatur.alcs.co.uk/IMP_FTP/privreportdef.pdf>.

-

Roger Clarke (1999) 'Identified, Anonymous and Pseudonymous Transactions:

The Spectrum of Choice' IFIP User Identification & Privacy Protection

Conference, Stockholm, June 1999 - at <http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/DV/UIPP99.html>

-

Roger Clarke and Gillian Dempsey (1999) 'Electronic Trading in Copyright

Objects and Its Implications for Universities', Australian EDUCAUSE'99

Conference, Sydney, 18-21 April 1999 - at <http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/EC/ETCU.html>

(visited 19/6/1999)

-

Julie Cohen (1997) "Some Reflections on Copyright Management Systems and

Laws Designed to Protect Them," 12 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 161 (1997) - at

<http://www.law.berkeley.edu/journals/btlj/articles/12-1/cohen.html>

-

Julie Cohen (1996) "A Right to Read Anonymously: A Closer Look at 'copyright

management' in Cyberspace", 28 Conn. L. Rev. 981 (1996) - at <http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/property/alternative/Cohen.html>

-

Brad Cox (1994) 'Superdistribution' Wired Archive | 2.09 - Sep 1994 - at

<http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/2.09/superdis.htm>

-

Coalition for Networked Information (1994) Proceedings: Technological Strategies

for Protecting Intellectual Property in the Networked Multimedia Environment

- at <http://www.cni.org/docs/ima.ip-workshop/>

-

William W Fisher III 'Property and contracts on the internet' (draft paper),

presented at the 1998 Internet Law Symposium Science & Technology

Law Center, Taiwan, June 1998 - at <http://eon.law.harvard.edu/property/alternative/98fish.html>

-

Daniel J Gervais (1998) 'Electronic Rights Management and Digital Identifier

Systems' - The Journal of Electronic Publishing Volume 4, Issue

2 March 1998 - at <http://www.press.umich.edu/jep/04-03/gervais.html>

(visited 22/6/99)

-

Graham Greenleaf (1999) ''Victoria's draft Data Protection Bill - The new

model Bill?'' 5 Privacy Law & Policy Reporter 36 - at <http://www2.austlii.edu.au/~graham/cyberspace_law/Vic_Bill.html>

-

Graham Greenleaf (1998) 'An Endnote on Regulating Cyberspace: Architecture

vs Law?' (1998) University of New South Wales Law Journal Volume 21, Number

2 'Electronic Commerce: Legal Issues For The Information Age', November

1998 - at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/unswlj/thematic/1998/vol21no2/greenleaf.html>

-

Graham Greenleaf (1996) 'Privacy principles -- irrelevant to cyberspace?'

(1996) 3 PLPR 114 - at <http://www.austlii.edu.au//au/other/plpr/vol3No06/v03n06d.html>

-

International Federation Of Reproduction Rights Organizations (IFRRO),

Committee On New Technologies, Digital Rights Management Technologies

- was, but no longer at <http://www.ncri.com/articles/rights_management/>

-

Kevin Kelly 'New Rules for the New Economy' WIRED archive 5.09 September

1997 - http://www.wired.com/wired/5.09/newrules.html

(visited 16/6/1999)

-

Robert Lemos 'Intel to electronically ID chips' ZDNet News 21 January 1999

- at <http://www.zdnet.com/zdnn/stories/news/0,4586,2189721,00.html>

-

L Lessig `The Law Of The Horse: What Cyberlaw Might Teach' - <http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/works/lessig/law_horse.pdf>

(June 11 1998 draft - visited 14/9/98) and <http://stlr.stanford.edu/STLR/Working_Papers/97_Lessig_1/index.htm>

(Stanford Technology Law Review Working Papers 1997 draft)

-

Charles C. Mann (1998) "Who Will Own Your Next Good Idea?" Part II, The

Atlantic Monthly, September 1998 - at <http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/98sep/copy2.htm>

-

Anita Smith and Roger Clarke (1999) Identification, Authentication and

Anonymity in a Legal Context' IFIP User Identification & Privacy

Protection Conference, Stockholm, June 1999 - <http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/DV/AnonLegal.html>

-

Mark Stefik (1997) 'Shifting The Possible: How Trusted Systems And Digital

Property Rights Challenge Us To Rethink Digital Publishing' Berkeley

Technology Law Journal, 12, 1 (Spring 1997) - at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/journals/btlj/articles/12-1/stefik.html

(visited 19/6/1999)

-

The Working Party On The Protection Of Individuals With Regard To The Processing

Of Personal Data - see 'Article 29 Committee'

[1] Almost

always attributed (without any source) to Stewart Brand, Electronic Frontier

Foundation Board member, and founder of the Whole Earth Catalog and the

WELL. See later concerning the full quote.

[2] See

Part II of Greenleaf 1998

[3] Barlow

1993

[4] 'Digital

works' is used loosely in this article to refer to any digital artefact

that could be the subject of copyright, including both 'works' (literary,

dramatic, artistic and musical) and other subject matter (films, sound

recordings etc).

[5] `Code

Replacing Law: Intellectual Property' in Lessig 1998

[6] One

list of famous quotes adds `Among others. No telling who really said this

first.' - <http://world.std.com/~tob/quotes.htm> (visited 15/10/98).

However, John Perry Barlow insists (though he still doesn't give a source)

that the full version of Brand's quote is: 'Information wants to be free

-- because it is now so easy to copy and distribute casually -- and information

wants to be expensive -- because in an Information Age, nothing is so valuable

as the right information at the right time.' (Barlow, in an Atlantic Monthly

Roundtable - at <http://www.theatlantic.com/unbound/forum/copyright/barlow2.htm>).

I'll stick to my imaginary version.

[7] See

Bygrave and Koelman [5.2] for examples.

[8] Bygrave

and Koelman emphasise this a little too much in Chapter 5.

[9] Kelly

1997

[10] Lemos

1999

[11]

For Microsoft's own confessions, see <http://www.microsoft.com/presspass/features/1999/03-08custletter2.htm>

[12]

ibid.

[13]

For extensive technical papers on various technologies, see Coalition for

Networked Information (1994)

[14]

This summary draws on discussions in from the following articles: Clarke

and Dempsey 1999; Stefik 1997; Cohen 1997a; IFRRO

[15]

For example, works protected by Softlock are freely copyable and partially

readable 'demos', but become full-featured once a password is purchased.

They automatically revert to demos when copied to another machine. Softlock's